As the world’s nations labour to vaccinate their citizens, the ever-evolving COVID-19 virus is spinning out highly transmissible mutant strains that are overwhelming our ability to contain and manage coronavirus within society. Faced with a dismally small global immunisation rate of about 10%, lockdown-fatigue leading to the premature relaxing of control measures, and the overdue recognition that airborne transmission is the main vector of spread, there is a pressing need for indoor air quality experts to step up and offer viable solutions.

Micro variants, macro changes: Everything's changing, maybe even language

The microbiological battle royale: a brief history of the biggest and baddest COVID variants

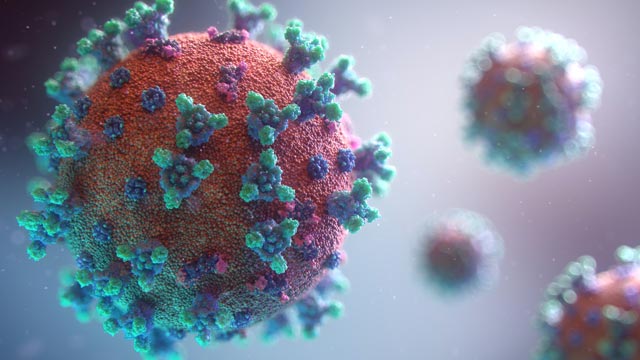

We’re all amateur immunologists these days, so we’re acutely aware that since first poking its spiky crown out from under our blanket of complacency in early 2020, the novel coronavirus / COVID-19 / SARS-COV-2 (or as it is now known, ‘the virus’) has undergone multiple mutations as it has spread throughout the globe.

Demonstrating the evolutionary principle of ‘survival of the fittest’, a select few of these COVID mutations have prospered, crowding out their competitors largely by virtue of adaptations that have made them more transmissible.

Since this microbiological battle royale began, regal status has been conferred to multiple contenders. One of the first COVID bluebloods to prove its pedigree was the UK variant, which emerged around the end of 2020 in London and nearby county Kent in England. It quickly spread throughout Western Europe and had become the dominant COVID strain in the US by April 2021. It was the first VOC designated by the World Health Organization (WHO), labelled as the Alpha variant (B.1.1.7), along with its tag-team partner – the Beta variant (B.1.351) – which was simultaneously wreaking havoc in South Africa.

Less than a month later the WHO bestowed the ignominious VOC moniker to Brazil’s Gamma variant, enlarging the viral monarchy to three. Each of these strains of the original SARS-COV-2 virus have their own unique attributes, resulting from variations on its spike protein – the molecule that allows the virus to bind to and infect human cells.

Alpha was thought to be slightly deadlier than its precursors while Beta is possibly more vaccine and antibody-resistant. But common to Alpha, Beta, Gamma and the recent fourth and perhaps most worrying VOC designation – India’s Delta strain – are dramatically increased levels of infectiousness that have seen the virus rip through populations with alarming speed.

Delta bad hand: why the latest Coronavirus variant might be the most dangerous yet

How bad is it doc? Give it to me straight…

- On average, the viral load recorded when a person first tested positive to Delta was ~1000 times higher than with the original virus;

- The period between initial infection and the point when a person tests positive for Delta is shorter than with the 2020 COVID strain, at around 4 days versus around 6 days.

“…this (Delta) is the one virus, we’ve contradicted ourselves in the past on this, we’ve said ‘This new variant – the Alpha variant – is infecting people unprecedentedly fast,’ and it’s turned out not to be true, it’s often in the early stages of an outbreak of a new variant when you think it is, but it isn’t.

But it turns out with this variant – Delta – it is turning out to be infectious from the time you’ve caught it until the time you transmit it. In at least one instance in Victoria it’s 29 hours, so that’s really a very short space of time…”

Clearing the air: waking up to the reality of aerosol transmission

With the early downplaying of airborne transmission and advice against wearing masks now widely recognized as a misguided response to a feared run on supplies of N95 masks, it is today clear that more often than not COVID is transmitted from person to person via aerosols, tiny respiratory droplets that can hang in the air for hours and hours.

Given Delta’s prodigious ability to replicate and quickly produce massive viral loads, it represents an unprecedented risk for airborne transmission, even during the most fleeting contacts where proscribed physical distancing is maintained. As Cassandra Berry – Professor of Viral Immunology at Murdoch University in Australia (a country currently experiencing outbreaks of the Delta strain despite some of the most risk-averse COVID policy settings in the OECD) – explains in this expert analysis of an outbreak of the Kappa variant in Melbourne in June:

“Fleeting encounters between infected and non-immune individuals can allow aerosolised virus particles to spread from human to human. Early during the infection cycle, the virus can simply leave the body through exhaled air or upper respiratory tract secretions. So no direct contact is required. These early days, especially when infected people do not show any symptoms or feel sick, can be critical for virus spread to new hosts.”

She goes on to stress the importance of other factors like the level of ventilation in internal spaces, and how “drying out conditions”, such as the dehumidification caused by many air-conditioning systems, can decrease the size of virus particles. These “smaller dried-out particles of viral droplets can be easily breathed in by other people in close proximity.”

Seeing the light: why we need to embrace UV air disinfection to fight this new VOC

Countries and economies are beginning to reopen despite the protests from medical experts who warn we are nowhere near the level of immunity for this to be done safely. But as Britain’s recent ‘Freedom Day’ encapsulated, after over a year of deferring to scientific caution an ideology that prioritises personal freedoms is becoming resurgent.

Despite rational fears that fully reopening before inoculation levels are anywhere near herd immunity levels will lead to dire health consequences, there is always hope. And one source of light at the end of the tunnel is, well, a light source – UVC germicidal light. This underutilised technology is proven to deactivate all known microbes, including airborne viruses like measles as well as the coronavirus.

When properly planned and installed, upper-room UV germicidal lights can operate safely and effectively in indoor spaces while people go about their usual business. Compared with complicated HVAC retrofits and HEPA filter installations, upper-room UV is affordable and low-maintenance.

Faced with extremely transmissible new variants like Delta, which pose a particular threat in terms of undetectable aerosol spread, it is time we look at the widescale adoption of upper-room UV air disinfection for an important added layer of protection.